Patents provide exclusivity

The owner of a patent can prohibit the use of that patent by others. The right to use a patent exclusively is the fundamental nature of a patent.

Standards, and especially interface standards such as Wi-Fi and 4G, use cutting edge technology to achieve maximum performance on their interface. And cutting edge technologies have patents associated with them.

Can patents prevent the use of a standard?

Developers of standards, the Standards Development Organizations or SDOs, obviously don’t like it when a patent owner blocks the use of their standard. The considerable effort that goes into developing a standard, typically hundreds of man-years, is wasted when that standard is not used.

What can an SDO do to avoid having its standard blocked by patent owners?

An SDO cannot prevent exclusive use of essential patents owned by non-participants

There is not much the SDO can do when the patent owner did not participate in the development of the standard. Companies that participate in developing a standard usually sign a contract with the SDO. That contract can create obligations for the participant that prevents the participating company from blocking the use of the standard by other companies.

Companies that didn’t participate in the SDO will not have signed such obligation and will remain free to use their patents exclusively. In other words, an SDO risks blocking when it inserts a patented technology into their standard without permission from the company that developed the technology.

These patents can prevent the use of a standard.

An alternative would be to rely on competition law, and argue that enforcement of the exclusivity of an essential patent is an anti-trust violation.

The anti-trust argument can work when a patent owner enforces its exclusive rights (by asking the court to stop the sales of infringing products) as a tactic to negotiate an unreasonably high royalty payment.

I am not convinced the anti-trust argument will work if the SDO included the patented technology without the consent of the patent owner, and the patent owner really does not want to license its proprietary technology. When courts permit the sales of an infringing product to continue, that permission is equivalent to a compulsory license. The circumstances, however, don’t seem to meet the criteria for compulsory license as set out in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

Essential patents owned by participants: the upfront promise to license essential patents

Some standards are developed by a group of companies. Such an “Industry SDO” signs a contract with each participating company. That contract can contain the obligation for the participating company to license its essential patents, usually on RAND (Reasonable And Non-Discriminatory) terms, sometimes royalty-free (RAND-RF). Companies not willing to sign such agreement will be denied the possibility to participate in meetings and will not be able to influence the choice of technologies made by the SDO.

When a company commits, before the technical specification is ready, to license its essential patents, that company cannot know which of its patents will become essential. The people responsible for the company’s patent portfolio don’t like such an open ended commitment. They will be concerned that patents the company uses to maintain exclusivity for its products will have to be licensed to its competitors and that the company will lose its competitive advantage. That is a valid concern, and particularly worrying when the SDO demands the commitment to license essential patents royalty-free.

The best way for the SDO to mitigate these concerns is to limit the scope of the license commitment to products (or even narrower, to the features of a product) that implement the standard and are fully compliant with the standard. This makes sure that other applications of an essential patent need not be licensed and can be used exclusively to differentiate the owner’s product.

Licensing essential patents makes business sense

When companies decide to participate in an SDO, they participate because it is in their commercial interest that the standard is successful. And standards are successful only when they are used by the entire industry. The promise to license essential patents makes, therefore, perfect business sense even when you don’t know yet which patents will become essential.

The remaining risk for a participating company is that the SDO develops a standard that is very different from what the company expected, including features that the company didn’t want standardized, or maybe even a standard with a completely different scope (“scope creep”). When an SDO requires the upfront commitment to license essential patents, the only protection against scope creep is to terminate membership before the technical specification becomes an official standard of the SDO. An SDO will usually not require commitments for standards that are created after a member has terminated its membership. An SDO that demands an open-ended commitment for standards created after termination of membership will have difficulty signing up members.

Scope creep is particularly problematic when the SDO requires the commitment to grand royalty-free licenses. When it is possible to collect royalties on essential patents the owner is compensated for the use of the patents, and when competitors use the standard and pay for using the patent that creates a useful cost-advantage. With royalty-free licenses there is no competitive advantage left. The patent becomes worthless. That’s why the companies with large patent portfolios will hesitate to join an SDO with royalty free license obligations or insist on very narrow scope limitations in the promise to license essential patents.

In any case, companies need the possibility to bail out (terminate their membership) of the SDO, and limit their commitments to standards that were created before they terminated.

Essential patents owned by participants: opt out when technical specification is ready

The alternative to an upfront commitment, is allowing participating companies to announce, after the standard’s technical specification is ready and before it is published, that they will not license their essential patents.

Such an ‘opt out’ at that late stage is a risk for the other participating companies. The standard is dead (cannot be used) if one of the participating companies refuses to license its essential patents. The other participating companies then lose their investment in the creation of the standard. That investment can be significant when the standard took years to develop.

An Industry SDO that was established with the purpose to develop a single standard can avoid that risk by creating the obligation to license essential patents upfront. That is acceptable for most companies. An SDO that develops many different standards, will discover that participating companies are far less willing to give prior commitment to license essential patents for all standards that this SDO develops. Such a broad promise to license patents is problematic for companies with a diversified product and patent portfolio because it will allow the SDO to use patented technology in standards that are not interesting for the patent owner, even when the owner never participated in discussions about that standard.

These multi-standard SDOs usually allow participating companies to opt out during a so-called “patent review period”. The patent review period lasts a couple of months between finalizing the technical specification of the standard and the decision to make that specification a standard of that SDO. During this time, the participating companies can study the technical specification and determine whether or not to license their essential patents.

A possible alternative would be for a multi-standard SDO to limit the promise to license essential patents to the sub-set of standards for which the company participated in the development.

When participants are not the patent owners: complications

The possibility to bind patent owners contractually is not available for an SDO when the participants are not companies but individual engineers (e.g. IEEE), or regional SDOs (e.g. IEC, ISO). These SDO’s cannot prevent individual engineers from promoting the use of patented technologies, owned by the companies that pay the engineer’s salary because they can’t force these companies to sign a contract. And the individual engineers usually don’t have the authority to sign contracts on behalf of their company. It is therefore not possible to ask individual participating engineers to commit to the license of essential patents on behalf of their employer.

These SDO have to take a more indirect route by creating obligations for the individuals participating in standards meeting. See, for example, the IEEE-SA Standards Board bylaws section 6.2:

“In order for IEEE’s patent policy to function efficiently, individuals participating in the standards development process: (a) shall inform the IEEE (or cause the IEEE to be informed) of the holder of any potential Essential Patent Claims of which they are personally aware and that are not already the subject of an Accepted Letter of Assurance, that are owned or controlled by the participant or the entity the participant is from, employed by, or otherwise represents; and (b) should inform the IEEE (or cause the IEEE to be informed) of any other holders of potential Essential Patent Claims that are not already the subject of an Accepted Letter of Assurance.”

The information collected about essential patents is used to ask the patent owners to confirm their willingness to license the essential patents. These obligations for the participating individuals create, indirectly, a somewhat fuzzy obligation for the employer of the participating individual to disclose its essential patents and state its willingness (or refusal) to license these essential patents before the technical specification becomes an official standard.

Patent Disclosure Obligations: useless

Not only the IEEE uses patent disclosure as a tool. Some Industry SDOs also ask the participants to disclose which patents they believe may be essential for the standard.

It is a great idea to have a list of essential patents ready when the standard is finished and to know whether or not each owner is willing to license the patent.

Unfortunately, it does not work. There are two fundamental flaws: (a) the list is unavoidably incomplete, and (b) the list will contain many patents that are not essential.

The list is unavoidably incomplete because it is very time-consuming (expensive) to review specifications and figure out which patents are essential. Most companies will not invest the time to contribute to such a list. They will simply report what an individual engineer happens to know, or not report at all. More worryingly, patent applications that have not been granted yet remain invisible, and the process under-reports patents owned by non-participants. This may lead companies to underestimate the risk that a patent owner will block the use of the standard.

The list will contain non-essential patents because it is expensive to objectively verify whether or not a patent is essential. Objective verification requires a claim chart and an independent reviewer. A list of essential patents, diluted with a large number of non-essential patents is misleading, and may cause companies to overestimate the risk that patents will prevent the use of a standard.

Single purpose Industry SDOs: simple and fast

An Industry SDO that develops a single standard can easily oblige the participating companies upfront to license their essential patents. That is the simplest way to make sure that participating companies will not block the use of the standard. And for the participating companies it is a low risk commitment when the SDO develops a single standard that the company needs for its business.

That is one of the reasons why industry standards usually have their own dedicated Standard Development Organization. There are hundreds of them: USB.org, Bluetooth SIG, Blu-ray Disc Association, Wireless Power Consortium, ….

Further Reading

See “Intellectual Property Licensing” about developing license programs that promote the use of standards.

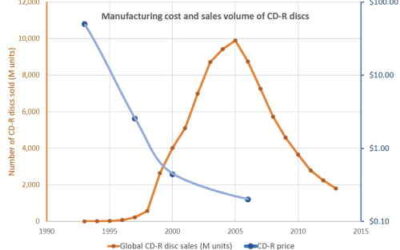

The article “The effect of patent royalties on the adoption of standards” analyses the consequences of royalty payments.