A guide for facilitators

The work of the facilitator of a multi-party negotiation between companies starts long before the participants can negotiate the terms and conditions of their agreement.

First, the facilitator must bring the participating companies together. In the early stage it may not even be clear who to invite, and how to convince these companies to join the negotiation.

The negotiations themselves will go quickly with the right preparation. A good facilitator will avoid the common pitfalls that can make multi-party negotiations so terribly slow.

1. Practical guidelines for a specific case

Multi-party negotiations exist in many different forms. It is possible to provide practical guidelines by narrowing down the circumstances to a very specific type of multi-party negotiation:

- Negotiations between companies (not between countries or individuals).

- The deliverable of the negotiation is an agreement to cooperate. That cooperation could be about developing a technical specification, or about jointly developing a service or product.

- The number of participating companies can increase or decrease during the negotiation.

- The result is subject to network effects. It is not a zero-sum negotiation (dividing a fixed size pie), but the value for the participants increases with the number of participants.

- There is no dominant party, dictating terms to other participants.

This type of negotiation takes place when companies want to make their products compatible by standardizing the interface between their products, or when companies want to jointly develop a product, or when companies want to jointly license their patents by creating a patent pool.

2. How to bring companies to the negotiation table

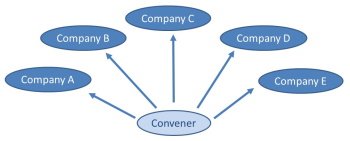

It usually starts with one company that identifies an opportunity for cooperation. A representative of that company reaches out to other companies with a proposal, the “term sheet”. The representative is called the “convener”.

It usually starts with one company that identifies an opportunity for cooperation. A representative of that company reaches out to other companies with a proposal, the “term sheet”. The representative is called the “convener”.

2.1. Create the initial term sheet

The first version of the term sheet can be as simple as a couple of PowerPoint slides, or a more extensive white paper. It should not look like a finished contract because at this stage, the convener is looking for feedback about the initiative. Other companies may have better ideas, or different ideas, and it is necessary to learn and adapt.

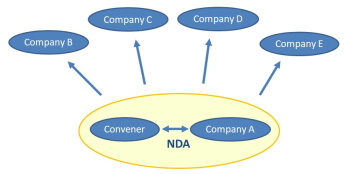

It is time to sign a multi-party NDA when the convener has convinced one or two other companies that it is worthwhile to investigate the opportunity.

2.2. Sign a multi-party NDA

This can be a vanilla reciprocal multi-party NDA with one special clause: it must be possible to add more companies to the NDA without going through the process of getting the NDA re-signed by everyone.

Parties agree that one or more additional companies may become a party to this Agreement if so confirmed in writing by all Parties. Each additional company will need to accept the terms of this Agreement and sign Annex 1.

2.3. Refine the term sheet and reach out to more companies

The group that signed the NDA can now reach out to other companies. The initiative is no longer presented as the initiative of a single company. The initiative will look increasingly attractive when more and more companies join.

The group that signed the NDA can now reach out to other companies. The initiative is no longer presented as the initiative of a single company. The initiative will look increasingly attractive when more and more companies join.

The term sheet is now refined by adding in details about the deliverables and about the governance of the proposed cooperation.

The high-level requirements for the deliverables of the cooperation need to be written down, together with an outline of the project plan for creating the deliverables.

The governance section of the term sheet deals with:

- How decisions will be made, by consensus or majority voting.

- Whether a form of legal entity will be needed, or that a joint development agreement is sufficient.

- Intellectual property license terms and conditions.

- How expenses will be shared, for example by collecting membership fees.

Each interaction with a prospective new member of the multi-party negotiation gives you feedback on the term sheet and may be reason to refine the document or even change aspects that were already agreed.

2.4. Dealing with incompatible demands

Participants will have conflicting demands. The group has a couple of options:

- Make a choice, for example by voting. That works well when the vote can be decided with an overwhelming majority. The company that lost the vote may leave if the choice makes it unattractive to invest.

- Make the decision depend on the outcome of an investigation. That can work if the debate is about technical feasibility. That investigation can be done before the start of contract negotiation, or after the contract negotiations have finished and the contract has been signed.

- Remove the contentious topic from the term sheet, and deal with it during contract negotiation. Usually not the best option.

Example

A group needs to agree an intellectual property policy when the goal of the cooperation is to develop an interface specification. There are two options: (1) members must grant users of the interface spec a royalty-free license (“RAND-Zero”) or (2) members may ask users of the interface spec to pay a reasonable royalty (“RAND”).

This choice has significant impact on the business case of participating companies. It is not advisable to delay a decision like this. Topics with significant impact on participant’s business are best decided before the start of contract negotiations. Participants who don’t like the decision will leave, whether the decision is taken now or later during contract negotiations.

2.5. Dilemma: more specific or more members?

It will be easier to agree the term sheet when all contentious topics are removed. Phase 2, (the contract negotiations) can start earlier, more companies participate. It looks tempting.

The problem is that the contract negotiation phase is very expensive for the participating members. Much more expensive than discussions about the term sheet, because the participant’s legal counsels get involved and they are scarce resource in most companies.

The multi-party negotiations will go faster when you spend more time dealing with contentious topics ahead of the actual contract negotiation. It is worth deciding the most important controversial topics in this stage, even when that results in companies leaving.

That creates a dilemma when relevant companies threaten to leave and may decide to start a competing initiative. When everyone is kept onboard by removing a contentious topic, the conflict will probably resurface later. In some cases that may be preferable.

Example

The initial term sheet of the initiative that established the Wireless Power Consortium contained the requirement that the technical solution would be based on a technology called “closely coupled magnetic induction”. One of the participants wanted to leave the decision on the technology open. The other participants didn’t agree and that one participant left. That participant later founded another industry alliance that developed a competing interface specification based on a technology called “loosely coupled magnetic resonance”. The result was a standards battle that was fought in the market by developing and selling products that used one of the competing specifications.

If the founders of the Wireless Power Consortium had agreed to leave the choice of technology open, that battle would have been fought inside the Wireless Power Consortium instead of leaving the decision to the market. See also the section “Developing competing standards: separate organizations needed?” in the article “Managing Competition Between Interfaces”

3. How to facilitate multi-party negotiation of a legal text

When the participants have agreed the term sheet it is time to work on the agreement. This should go quickly when the term sheet has enough detail.

It is essential that a neutral faciliator guides this stage of the multi-party negotiation. Ideally, someone who is not affiliated with one of the participants. The facilitator can also be an employee of one of the participants provided another employee represents their company in the discussions.

It will also help to also engage a neutral legal counsel to create the initial draft and revise the draft after each round of discussion.

3.1. Create the initial draft agreement

One of the participants, the facilitator, or the neutral legal counsel can propose a first draft of the contract. This draft works out the content of the term sheet in formal legal clauses and adds legal boiler plate clauses.

3.2. Review by the participants

Each participant reviews the draft contract and provides comments.

Comments fall in two categories:

- Editorial: these are obvious improvements that don’t need an explanation.

- Substantial: these identify a problem in the draft and may (optionally) suggest a solution.

To make the negotiation process work efficiently, it is necessary that each substantial comment contains an explain of the perceived problem. The facilitator must refuse to discuss substantial comments without an explanation of the problem.

3.3. Discuss the comments

The facilitator collects all comments into a spreadsheet with these columns:

- Number of the clause

- Name of the participant who submitted the comment

- Description of the perceived problem

- Solution proposed by the participant (optional)

- Classification by the facilitator (major, minor, editorial)

- Analysis by the facilitator

- Proposal by the facilitator to address the problem

The facilitator distributes the spreadsheet to the participants and organizes a meeting of the participants to discuss the comments.

In this meeting, the participants only discuss the spreadsheet. Don’t do a page by page review of the text of the draft agreement with the entire group (see common pitfalls).

The discussion in the group can be limited to the major comments.

For the minor and editorial comments, the facilitator can ask the participants: “does anyone wants to discuss an editorial/minor comment?” or “do you agree with the proposed solutions for all editorial/minor comments”?

3.4. Revise the draft

The facilitator implements all decisions in a revised draft agreement. Another round of review is started. These rounds of review, discussion, and revision continue until the participants are ready to sign.

4. How to avoid common pitfalls in multi-party negotiations

Speed is important. The group will work more efficiently when you avoid these five mistakes:

4.1. Don’t give participants much time for review

Each round of review, discussion, and revision should take no more than a week.

Longer time between rounds makes participants forget the details of the agreement. They need to spend more time reviewing the revised draft and may re-open discussions that were decided before. It also increases the probability that companies change the negotiator or the corporate legal counsel representing them. And that will disrupt the process and cause even more delay.

A series of weekly meetings must be scheduled in advance, before the start of the contract negotiations, to make sure that all participants are available.

4.2. Don’t wait for consensus

You cannot expect everyone to agree with all proposals to change the draft agreement.

The most difficult discussions are when disagreement is caused by a difference in business interests. Such a problem cannot be solved by continuing the debate. At some point the group needs to decide. It can help to bundle all remaining issues together and make a deal about the bundle.

The group needs to know that decisions will be taken, also when a small minority objects. That is an incentive for minorities to find a compromise and move on. If that fails, the consequence may be that one of the participants drops out and refuses to sign the final agreement.

4.3. Don’t fake consensus with ambiguous language

It is tempting to solve the conflict by reformulating the text of the clause until everyone agrees with the text. The result will be an ambiguous text (interpreted differently by the participants) when the underlying difference in business interest is not addressed.

Be aware that the problem will re-surface later, after the agreement is signed, during the execution of the project. That may be a deliberate choice if it is essential to keep everyone on board, but it usually a bad practice.

4.4. Don’t review the agreement page by page in a group meeting

When you review a draft agreement page by page with a group, participants will read through the agreement and come up with ad hoc comments that have not been thought through. The most disruptive comments are made by participants who have not even bothered to read the agreement before the meeting.

The participants have an incentive to do their homework on time, and negotiations will conclude faster, when only comments in the spreadsheet are discussed.

4.5. Don’t leave negotiations to the lawyers

Is it possible to leave the contract negotiations to the participants’ corporate lawyers?

In my experience that is not the way to finish the contract negotiations quickly.

The reason for drafting the contract is that the participants want to cooperate to develop a technical specification or a product. The technical requirements are in the term sheet that has already been agreed at this stage, but issues relating to technology and planning of the cooperation will come up during contract drafting.

Ideally, the negotiation team of each participant is headed by the person who will manage the company’s participation after the agreement has been signed, supported by their legal counsel, with the business owner available in the background to decide on compromises.

5. Further reading

There is an extensive literature on multi-party negotiations. Most of it is about zero-sum game negotiations, or written from the point of view of the negotiator, with little guidance for the facilitator.

The following articles may be useful:

- Do’s and Don’ts When Engaging in International Multi-party Negotiations, by Arnold Brown, gives suggestions for the participants in standards development.

- https://www.negotiations.com/articles/multiparty-solutions/

- https://thebusinessprofessor.com/en_US/communications-negotiations/multiparty-negotiations